Protect Memory: the Shoah, Gaza and History

My talk for the Italian University workers for Palestine Network

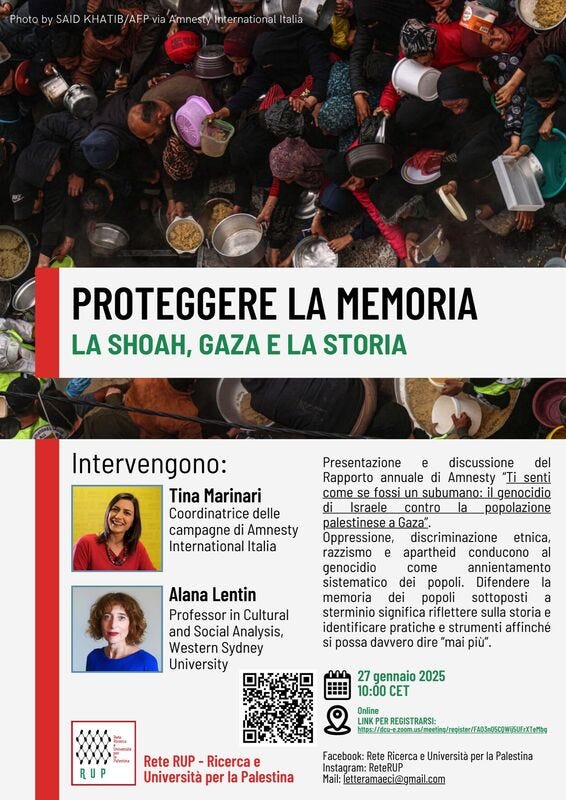

I was asked to speak at an important event organised by the Italian University workers for Palestine Network to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January 2025, Proteggere la Memoria: la Shoah, Gaza e la storia (Protect Memory: the Shoah, Gaza and History).

27 January has been the annual International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust since 2005. As someone who has been living in the settler colony known as Australia for over ten years, it is notable to me that it comes a day after what is known here as ‘Invasion Day,’ the day on which the British invaded the continent in 1788, 237 years ago.

Officially, the date is referred to as Australia Day. It was instituted as a national holiday by a Labor (centre-left) Prime Minister, Paul Keating, only in 1994, but earlier, white nationalists who were in favour of preserving the racist ‘white Australia policy’ lobbied for it as early as the 1930s. Indigenous people first marked January 26th as a Day of Mourning by holding a protest on that day in 1938. This year, thousands of people marched in capital cities around the continent to recall that genocide against Indigenous peoples is ongoing. Where I was, in Sydney, family members of people murdered by the police or prison guards, or whose children are forcibly removed by the state spoke, appealing to the public to raise the alarm, to pay reparations for the loss of life, land and culture, and to bring down the colony!

I start with this because, although the fact that the two dates - Invasion Day and Holocaust Remembrance Day - are so close to each other is purely coincidental, it reminds us of the very different ways in which the two are commemorated. Australia’s right-wing opposition leader is currently attending a Holocaust commemoration in Poland. At the same time, he rejects the popular calls to stop celebrating ‘Australia Day’ on the day of invasion and is opposed to the official display of the Aboriginal flag.

But moral panic about political figures on the right can lead us to ignore that even those on the centre-left use the memory of the Holocaust to shield their support for and participation in genocide. This is most clear in the case of Palestine. The last fifteen months in Gaza, and what is unfolding in the West Bank and Lebanon, should remind us that this is but the latest phase in a 76 year-long genocide by Zionists of the Palestinian people. This genocide has been justified by antisemitism and the memory of the Holocaust; it has been touted as necessary in order to prevent another Holocaust, even as Israel and Zionists openly collude with political figures who have engaged in Holocaust denial, or who come from movements and parties that are openly antisemitic, such as Marine Le Pen or Viktor Orbán.

As Elon Musk said, following his performance of the Nazi salute at Trump’s inauguration, “apparently I’m a Zionist and a Nazi” (followed by a few laughing emojis). The idea is that these two positions should be mutually exclusive, but both recent and longer history instruct us that this is far from the truth. As things stand, official memorialisation of the Holocaust stands in the way of antiracist knowledge and action.

In the rest of my talk, I will expand a little on the political ends to which the hyper focus on antisemitism is being put and make some critical remarks about the idea of the ‘weaponisation of antisemitism,’ which I think is a misnomer. I then will speak about the way institutions are using what the Palestinian scholar, Anna Younes, calls the ‘war on antisemitism,’ through the idea of racism and antisemitism as a ‘hate crime,’ to police and punish antiracists. In conclusion I will say some words about how to continue to talk about antisemitism in light of how it is used to repress and punish, not only speech and protest on Palestine, but radical antiracism and anticolonialism more broadly.

The political ends of the Holocaust and antisemitism

Early on in this phase of Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians, we were shown clearly how the Holocaust was going to be used a political tool. Israel’s UN representative wore a yellow star inscribed with the words ‘never again and said, ‘We will wear this star until you wake up and condemn the atrocities of Hamas.’

The phrase ‘never again is now’ competes with ‘never again for anyone.’ The second phrase acknowledges, not only that the Nazi Holocaust did not target Jews alone - a fact that still involves significant political battles - and that it built upon 500 years of colonial genocides, but that it applies in the present to Israel’s actions.

The first phrase links specifically to Operation Al Aqsa flood. For example, the German Federal Minister Nancy Faeser said in a speech commemorating the anniversary of Kristallnacht in 2023, that,

“Germans today must never remain silent or look the other way when Jewish people are attacked and murdered – as they were in Israel on 7 October, by the Islamist terrorist organisation Hamas. Hamas terrorists cold-bloodedly hunted down men, women and children with the intention of killing as many Jewish people as possible. More Jews were killed on 7 October 2023 than at any time since the Shoah… We mourn the dead. We feel with their friends and families. We fear for the hostages. And we stand by Israel. Unconditionally."

In fact, more Jews were killed when up to 3,000 leftist Jews were targeted as part of Argentina’s “Western and Christian” military dictatorship during the “dirty war” of the late 1970s, which was called “a specific anti-Semitic genocidal plan” in a report by the Commission of Solidarity with Relatives of the Disappeared (Cosofam) published in 1999. But the relationship between Israel and the regime in Argentina, among other Latin American fascist regimes, means that this history remains hidden. For a good analysis of this history, I recommend listening to the historian Alexander Aviña interviewed on the Guerrilla History podcast.

The idea that Hamas has surpassed the Nazis in its murderous hatred for Jews has permitted a perverse from of Holocaust denial to be condoned and celebrated. For example, the right-wing British journalist, Douglas Murray wrote in The Jewish Chronicle that ‘the civilised world should seek revenge’ and ‘back Israel and back the destruction of Hamas.’ It is right to do so, he wrote, because ‘nothing could surpass the barbarism of what Hamas did’ on October 7. Murray argued that the Nazis were civilised because they were not proud of what they did to the Jews. This is unlike Hamas who, he said, murdered Jews with glee. This places them on the side of the barbarians and justifies all action against Palestinians in retaliation.

Fast-forwarding fifteen months later, and the election of Trump, Elon Musk’s Nazi salute is explained by the Zionist-Jewish organisation, the Anti-Defamation League, as “an awkward gesture in a moment of enthusiasm, not a Nazi salute.” But, talking about these seeming paradoxes feeds into a narrative of hypocrisy that does not help us to understand their origin or purpose. Elon Musk’s remarks about being both a Nazi and a Zionist play into the idea that one cancels the other out. Likewise, going to war ostensibly against antisemitism cancels out the idea that killing Palestinians is either racist or genocidal. From this point of view, in fact, it is possible to argue that the last 15 months in Gaza have been antiracist. And Zionists have argued this.

Yet talking about this as hypocrisy denies the fact that racism is actually premised on hypocrisy; that it is not only possible, but right to do to one group what cannot be done to another. This was put most plainly by Isaac Herzog, President of Israel, in December 2023 when he said,

‘This war is a war […] that is intended - really, truly - to save western civilization, to save the values of western civilization.’

It is not hypocritical to apply different standards of what constitutes genocide when it comes to Jews and Palestinians, because the very concept - as anticolonialists such as Frantz Fanon or Aimé Césaire said long ago¾ - is a Eurocentric one that is based on an understanding of humanity as a hierarchy. Europeans are at the top of this hierarchy and their lives are more worthy of preservation. Moreover, the greatest threat to European life is posed by non-Europeans; it is thus justifiable, and even commendable, to extinguish what is posed as an existential threat to ‘our’ safety.

How Jews came to be seen as integral to the preservation of western, European safety needs more time that I have today. In short, my argument - one I expand on in my forthcoming book, The New Racial Regime: Recalibrations of white supremacy - is that the figure of the Jew comes to stand for westernness, Europeanness and whiteness at a time when it was no longer politically possible to openly stake a claim to white/western/European supremacy.

Antisemitism operates through what the decolonial thinker Houria Bouteldja calls ‘state philosemitism’, in which Jews are recruited as a buffer class between the state and the masses. What is clear today is that this has facilitated, not only the genocide of the Palestinians, but a return of open, prideful white, western supremacism. Israel stands as an example of all which the West is determined to be. Following its example, to paraphrase Donald Trump, would allow the West to be “great again.” This is indeed the argument of figures like Douglas Murray who argues that Israel is an example to its western allies because it is a strong nation where ‘nationalism is viewed as good, and patriotism is good.’ He proposes to turn to the example of Israel in order to resist the decline of western civilisation, and save it from ‘mass immigration.’

In fact, what we are seeing is what the West has always been projected back to itself. It is wrong to see Israel and Zionism as an outlier case. Rather they are the current manifestation of a racial-colonialism that is European in origin and design. Zionism could only have been envisaged within the context of European nationalism and global imperialism. It relied on European antisemitism to make its case. As Arthur Balfour argued in his pitch for Zionism, the creation of the Zionist state would “mitigate the age-long miseries created for Western civilization by the presence in its midst of a Body which it too long regarded as alien and even hostile, but which it was equally unable to expel or to absorb.” He was talking about the Jews.

As the Director of the Palestine Research Centre, Fayez Sayegh said, the Zionist colonisation of Palestine took place against the backdrop of ‘the frenzied “Scramble for Africa.’ Like other settler colonies, Zionists established not only a colony ‘on Afro-Asian territory,’ but ‘a settler community’ much like Australia, Canada, Rhodesia or South Africa. And for Zionist founder Theodor Herzl, the Zionist state would be a ‘rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilisation as opposed to barbarism.’

It is partly for these reasons that I am wary of arguments that talk about the ‘weaponisation’ of antisemitism to repress pro-Palestinian speech and protest. On the one hand, as I have already stated, the hypocrisy is very much the point; racism operates according to a logic of double standards. Second, all forms of racism are intrinsic weapons. As Ruth Wilson-Gilmore notes, racism creates greater vulnerability to premature death for those whom it targets. So, we should talk more precisely about anti-antisemitism as a tool for the implementation of racialised control, discipline and punishment that targets those who are already most vulnerable to the state’s manoeuvres against them.

I now turn to examine some examples of what this looks like today.

The ‘war on antisemitism’

The most useful formulation of the way the ostensible fight against antisemitism is used to discipline and punish pro-Palestinian action was introduced by Anna Younes. Younes claims that the ‘war on antisemitism’ should be best understood as following a similar logic to the ‘war on drugs’ and the ‘war on terror.’ These confected ‘wars’ were designed by the state to rationalise the greater repression of populations who are seen as posing an intrinsic threat to western, white “safety.” Safety here should be understood as code for dominance.

These wars also have a neoliberal logic in that they facilitate what Gilmore calls ‘organised abandonment.’ This is where the state retreats from providing any protection to the most at-risk groups (from welfare recipients, formerly incarcerated people, to asylum seekers, and migrants, etc.). At the same time, it justifies this retreat by portraying these groups as posing a threat to the public. This sets up a vicious circle where the retreat of the state creates greater vulnerability which then exposes these groups to criminalisation as they struggle to survive (for example asylum seekers who are not allowed to work officially and who have to work in the ‘underground economy’ and are then criminalised for such).

While each iteration - the war on drugs, terror, or antisemitism - arises out of a specific set of domestic and geopolitical problems, they operate along similar logics. Crucially, they establish a narrative in which more and more repressive and carceral actions become acceptable among the public, which is motivated by the manipulation of fear. This process is described by Stuart Hall and his colleagues in the classic book, Policing the Crisis.

We can see how this works today in the use of the notion of ‘hate crimes’ and look at how this is being used specifically to repress action on Palestine.

The idea of racism as derived from hatred, and of antisemitism as the oldest form of hatred, is widely accepted. It contradicts a proper historical understanding of race as a technology for the management of human difference that emerges in Europe due to what the Black Studies scholar, Cedric Robinson, said was the “tendency of European civilization through capitalism” not to “homogenise but to differentiate - to exaggerate regional, subcultural, and dialectical differences into ‘racial’ ones.”

The elevation of hate as the mainstream explanation for racism assists the racial state by portraying racism as a matter of individual attitudes and prejudices. Hate can be ‘weeded out’ through either education or punishment, or both. A major proponent of this approach has been the Jewish-Zionist organisation, the Anti-Defamation League. While it originates in the US, its approach has had widespread global impact. It is involved in education, lobbying and policy. As Dylan Rodriguez has said, ‘the Anti-Defamation League has its roots in the repression of revolutionary, radical, anti-colonial and Black liberation movements. It’s been an anti-communist organisation, and it’s pushed forward the US domestic sphere of Nakba, anti-Palestinian repression [for] going on 80 years.’

Beyond the ADL itself, the widespread understanding of antisemitism as the ‘oldest hatred’ underpins the widespread repression that we see today. However, it is important to understand this not as new, but as the accentuation of practices that have already been in place for many decades. The main targets of this criminological politics have always been Black, Palestinian, and other leftist political radicals who are the targets of state counterinsurgency. If we understand the ‘war on antisemitism’ today in line with the ‘war on terror’ of the first two decades of the millennium, we also saw the mass repression and surveillance of Muslims for being critical of the actions of the US and its imperialist allies in Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and so on.

It is therefore fundamental to understand that any group or organisation that promotes the narrative of antisemitism as a hate crime and calls on the state to take action against it under this guise, is condoning this criminological and carceral approach, even if it does so from an ostensible stance of antiracism.

As many are aware, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Working Definition of Antisemitism has been another method used by Zionists to repress and punish anyone who speaks out in favour of Palestinians within public institutions, like universities. The IHRA is both a bad definition of antisemitism, proposing that it is a ‘certain perception of Jews.’ But, the major problem is that 7 out of the 11 examples provided of antisemitism relate to criticisms of Zionism and Israel. Taken together with the legislation of antisemitism as a hate crime, the adoption of the IHRA definition poses a particular problem because if its negative impact on antiracism. Institutions like universities often fold the IHRA definition into polices on diversity, equity and inclusion which are supposed to mitigate harm against groups at risk of institutionalised racism.

The attacks on the diversity, equity and inclusion by the Trump and other right-wing regimes in Europe, will not lead to a rolling back of the effects that the IHRA has had within institutions. Any approach to fighting these effects should not encourage the greater use of frameworks like DEI to define what racism is and is not, and how it should be tackled. Rather, groups need to struggle against the institutional cooptation and dilution of antiracist principles. As we have seen, there are rarely ways in which these can be used for truly radical ends.

In conclusion

How do we then talk about antisemitism and the memory of the Holocaust in light of the snapshot I have given today? There are many efforts being made to think about them relationally. Scholars such as Zoe Samudzi, and activists have proposed ways of thinking about the Holocaust continuously with colonial genocides. Others have stressed the need for solidarity between Jews and other negatively racialised groups. Many Jewish groups have been at the forefront of Palestine solidarity citing the Holocaust and antisemitism as a motivator for them. I am a participant in these efforts. However, I listen carefully to Palestinian critics, such as the Good Shepherd Collective, an organisation in Palestine, whose members warn that the central role accorded to anti-Zionist Jews can lead to a recentering of the significance of antisemitism as a key reference point for understanding racism, including racism by Jews against Palestinians.

I think it is very important to take this on board, not because Jews must diminish our history out of a sense of guilt for the present - a common affect within Jewish anti-Zionist organising - but because I believe that a view of racism that differentiates its various form is not useful from the standpoint of antiracism. While we can study the way different racisms take shape and develop, we are very simply for racism or against it.

The Zionist tactic is to distinguish antisemitism as a special form of racism that is portrayed as existing outside of history, in the atmosphere, and ever-present. This colludes with a racist reading of racism, often paradoxically upheld by liberal antiracist activists and researchers, that racism is the ahistorical product of perennial prejudices.

We may have to have some difficult conversations, but I believe these are fundamental in the time of fascism, that - for many - is already here.