Not Racism™, the Voice Referendum and white progressive anxiety

How white progressives are making the referendum, like everything else, all about them.

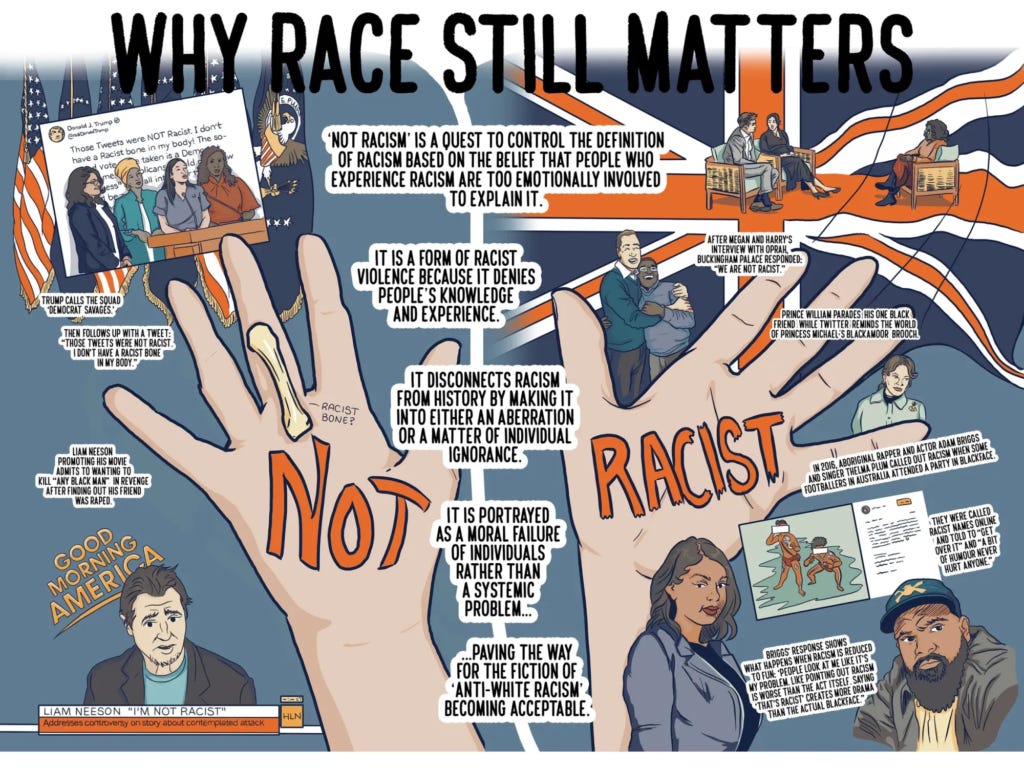

The lead-up to the referendum on the Indigenous Voice to parliament is replete with text-book case after text-book case of what I have called ‘Not Racism™’. Not Racism is something anyone who has faced racism knows about. In an article I published in 2017 on the subject, the title the editors gave to it was ‘I’m not racist but…’ But my argument goes one step further than noting that racists love to deny that they are racist. Rather, Not Racism is a quest to control the definition of racism and wrest it away from the experiential expertise of Indigenous and other negatively racialised people. Racism is turned into a disparate set of attitudes towards people who are different to oneself: a universal and free-floating moral posture that is severed from the history of race and the contexts in which it became a technology for the management of human difference, as I define it in my book Why Race Still Matters, contexts such as colonisation, Indigenous dispossession, slavery and indenture, racialised policing, and the violent border regime.

And so we have it again as we enter the last month before the referendum. Not Racism™ has been there from the start, undergirded by the strong presence of Indigenous No vote campaigners, such as Jacinta Price and Warren Mundine, whose appearance at the reactionary conservative C-PAC event in Sydney recently works to paper over the links between the Australian far-right and its fellow travellers across the Anglosphere. But Not Racism™ really ramped up following Professor Marcia Langton’s comments delivered in Western Australia on September 10th: ‘Every time the No cases raise their arguments, if you start pulling it apart you get down to base racism, I’m sorry to say that’s where it lands, or sheer stupidity.’ Needless to say, this led Liberal Party leader, Peter Dutton to retort via Instagram that Langton had called anyone who votes no ‘racist and stupid.’

This prompted headlines in the Murdoch Press and right-wingers such as Nationals senator, Matthew Canavan complaining that Australians were ‘sick and tired of being called racist.’

It has also been interesting to see the liberal, pro-Yes media take an indignant stance on behalf of Langton. Annabel Crabb, despite providing a soft landing for Scott Morrison and more recently Peter Dutton and whitewashing their roles in fortifying Australia’s brutal border regime, wrote, ‘We know that racism exists.

We know what it does to people.’ Katharine Murphy, in The Guardian, followed up with ‘talking about racism makes people uncomfortable. When the subject gets broached, an unsettling dynamic can ensue. People can appear more outraged by accusations of racism than about racism itself.’ It is almost as if Indigenous and other negatively racialized people haven’t been saying exactly this forever. In fact, Adam Briggs made almost the exact same point in 2016 when he spoke out about an incidence of blackface at a Western Australian football club: ‘‘People look at me like it’s my problem. Like pointing out racism is worse than the act itself.’

White liberal pro-Yes figures are becoming exercised by racism because of a preoccupation that has little to do with concern for Indigenous people, much less their self-determination and their demands for land back, and much more with how Australians appear to the outside world. Ever since I moved to this continent in 2012, I was struck by the anxiety that is expressed over and over again among white progressives over the optics of racism. There have even been TV shows such as the SBS documentary, Is Australia Racist? I am tempted to answer, ‘Is the Pope Catholic?’

The feeling was expressed in its most exemplary form in The Saturday Paper, an outlet which touts itself as progressive but which has been called out by Palestinian activists and, more recently, the former ABC journalist John Lyons, for its appalling record on Palestine. An article by Barry Jones in the weekly argued that the Voice referendum ‘is our Brexit.’ This conclusion is not come to through any deep engagement with the actual effects of Brexit on the British public, particularly the sharp decline into even greater economic inequality. Rather, this was all about a ‘bad look.’ Jones makes the claim that a defeat of the Voice on October 14 ‘would lead to a loss in international standing and influence – a perception, quite inaccurate, that Australia has not forsaken its racist past.’ He followed by predicting a ‘severe case of buyer’s remorse’ as No voters would realise what they had unleashed.

I find this astounding. Not only does it clearly demonstrate what the author’s real concern is: for Australia not to appear racist overseas. And not only does he believe that any perception that Australia is indeed a racist country is unwarranted because racism is safely in the past. More telling still is the fact that he believes that a No vote will have a tangible impact on the white settler population in Australia akin to Brexit for the British. In reality, a loss for the ‘Yes’ side will not have any material impact on the majority. We will still benefit from what Goenpul woman of the Quandamooka nation and critical Indigenous scholar, Aileen Moreton-Robinson calls the ‘possessive investment in patriarchal white sovereignty.’ In other words, white people will still own the majority of the continent’s resources. We will still benefit from living on land expropriated by force from its original owners. Non-white settlers may well suffer the blowback of the increased racism that will doubtless result from a successful No vote. But that racism has already been unleashed by the referendum itself, which many Indigenous people from both sides of the argument have said was unnecessary for the Voice to Parliament to be instituted.

What this whole debacle is making loud and clear once again is how little understanding exists in Australian society about what racism is. There is a widespread belief that it is possible to separate words and ideas from material realities; from laws, policies, and the actions of a colonial state that from its very inception used race to institute white domination. This is not an argument for or against the Voice, but it is a call to recognise the irony of calling out the racism of a Dutton or a Canavan while repeatedly making the claim that there is nothing to fear from an advisory body whose existence will not threaten the integrity of the Australian state, a state founded on stolen Indigenous lands and whose first Act of Parliament established it as a bastion of white supremacy. It is also telling that the sudden call to take racism seriously from pundits such as Crabb, Murphy and Jones make no mention of the inseparability of race as a technology for producing and maintaining global white supremacy and the destruction of the climate, something some of the Yes vote’s biggest supporters are playing an outsized role in advancing.

Whatever the outcome of the referendum, I have grave doubts about whether the workings of race will be better understood in the continent. To truly understand what race does would mean radically transforming the entire basis on which this society is organised, and for that there is very little appetite; certainly not from the white progressives whose voices are loudest in the media.